Recreating a set of Elizabethan Trenchers: an Introduction

Part of the appeal of researching early methods of print production is the possibility of recreating objects which use prints as part of their decoration or function. With this in mind, I decided to set about recreating a set of Elizabethan trenchers (also known as roundels). Because the method of production encompasses a number of steps and issues – the design, the prints, the wood, the assembly – the best way to tackle writing about this is to break the process down in to a number of articles. So this introduction is to give some information and background to the actual objects which have been the inspiration.

Elizabethan/late 16th century trenchers are a long way from their humble originals, the medieval (and earlier) trencher. Trenchers began as the flat slice of a flattish loaf of bread incorporating the top or bottom of the loaf, used as a plate. There’s a very nice article about medieval bread which includes trenchers here. It is thought that the word ‘trencher’ could come from either of two related French words, ‘tranchier’ (to cut) or ‘tranche’ (slice) – potentially subtly different meanings. None the less, what began as bread vessels turned into wooden ones, such as these from Abingdon-On-Thames in the mid-16th Century.

And as with anything which can reflect status, the trenchers which were owned by wealthier people became thinner and better finished, to show the craftsmanship they could afford. From there, it was not hard to see the development of the underside becoming a potential surface for decoration. In particular, it would seem that a trencher for the end of the meal, for cheese or sweetmeats, became a regular occurrence. This is described by Henisch in her book, Fast and Feast –

“If at no other stage in a meal, a clean trencher was expected at the very end, when cheese and little delicacies were brought in. The child addressed in The Babees Book is given this advice:

‘Whanne chese ys brouhte, A trenchoure ha ye clene On whiche withe clene knyf ye your chese mowe kerve.’

“From these ‘dessert’ trenchers developed miniature wooden plates, charmingly decorated on one side with flowers and improving texts, of which a few sixteenth and seventeenth examples still survive.”

The decorated and inscribed trencher was used in a specific way, which may seem unusual to us, but fits perfectly with the Tudor and Elizabethan mode of entertainment for high status dining. This was the age of magnificent subtleties (decorative and/or edible creations presented during dinner to entertain and delight one’s guests), and amusements such as gilded eggs or walnuts containing gifts. People loved the concept of disguising, of objects appearing to be one thing, but turning out to be another.

Narrative portrait of Sir Henry Unton (detail)

Artist unknown

Oil on panel

England c1596

At the end of the meal was the ‘banqueting course’, what we would now think of as dessert. Hippocras, wafers and sweetmeats would be served upon the thin, decorated trenchers – which were presented face down. The objective of this was two-fold – the first, most obviously, to protect the beautiful decoration. The second was the element of delight and entertainment – after the dessert was consumed, guests would turn over their trenchers and recite or act out the verse which was inscribed. If one would like to think of a decorated trencher as parallel to a modern-day fortune cookie or Christmas cracker, we are on the right track, albeit without the nuances that these objects would have had in period.

The words ‘trencher’ and ‘roundel’ appear to have been equally used once these objects began to be used as an object in their own right with a specific purpose, with roundel referring to the circular shape of the majority. There are indeed examples of these trenchers still in existence – some are single examples, some are partial sets, and a very few full sets, which were thought to usually be 6, 10 or 12 in number. In early development, they seem to have been mostly painted with flowers, with a poem or verse in the centre or around the rim. Amongst the extant examples, we can see a single, rather battered, painted example survives in the Bristol museum:

Trencher/roundel in the British Museum

Artist unknown

Wood, painted with flowers and verse

England c1525-75

A complete set with its accompanying box is in the Museum of London:

Trenchers and box in the Museum of London

Artist unknown

Beech, painted with flowers and verse, diameter 165 mm

Made in London c1601-35

And a less common rectangular example from the Metropolitan Museum:

Rectangular trencher

Artist unknown

Sycamore wood, painted and gilt, dimensions 116 x 144 mm

Britain early 17th century

As the Tudor era continued into the Elizabethan and Stuart eras, trenchers with printed images were produced. This is not surprising or unexpected, given the 16th century is the time when the merchanting and middle classes were gaining incomes far greater than they had previously, and were always eager to obtain or imitate those items which were desirable to and/or fashionable with the upper classes and nobility. By the birth of the 16th century, vast quantities of prints, both in relief and intaglio, were being produced to satisfy the wants and needs of the middle (and also lower) classes.

The word ‘roundel’, mentioned earlier, has also been the description applied to any form of circular decoration or decorative object, and may have been why trenchers were also referred to as roundels. A roundel may be a round stained glass window, a plaque for a wall (interior or exterior), an illustration in a book, either illuminated or printed, and so on.

Sets of printed roundels on paper dating from around the 1530s onwards exist in many collections, some as full or partial sets, on a variety of themes – the seasons, the months, the labours of the months, zodiacs, biblical stories, muses, Sibyls, flowers, famous people, Aesop’s fables, to name a few. They could be used by craftsmen in the same way as an artist’s cartoon (drawing), becoming design ideas for craftsmen such as gold- and metal- smiths, potters, plasterers, carvers, tilers, painters, and so on. And in the hands of a private purchaser, being a print, they could also be used by more people, and in many and varied ways. Printed roundels in this format were very popular and affordable to the middle classes, and would have been used for many and varied applications, coloured or uncoloured – wall decorations, pasting into books for illustrations and folios/albums for collecting, pasting onto and into boxes. Many of these were printed not only in England but Germany and the Netherlands.

Some extant prints have had their papers trimmed, ready for use, such as this example:

Roundel with an embracing couple and a male figure arguing with a soldier

Artist Unknown

Engraving or etching, diameter 41 mm

Germany 1520-1540

While other remain as uncut sets, such as the example below from a set in the British Museum, based on the intaglio prints of Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, published in 1567. Gheeraerts etchings of Aesop’s Fables were an immediate success and were copied many times over several centuries. This particular set was originally executed for Roger Daniell in the 1620s, and reprinted by Thomas Johnson in the 1630’s:

The bear and the honey-bees, a trencher copied from Gheeraerts’s illustrations to Aesop

From a set of twelve plates intended to be used as trenchers

Engraving, diameter 127 mm

Plates produced Netherlands c1620, reprinted Britain c1630

A telling sign that prints were designed to be trimmed and attached to round objects such as trenchers is the presence of multiple circles around the perimeter of the print – often including multiple verses, phrases and mottoes. These additions gave the purchaser extra flexibility to choose different sizes to suit their needs, with the print being trimmed to the desired size. There was also the option of trimming all text off the image, and handwriting something of one’s own choosing. This is one such example:

January, from the 12 Months in roundels

Copied from Crispin de Passe the Elder, published by Roger Daniell

Engraving, total dimensions 192mm x 135mm

London c1620-30

And so as with the painted versions of trenchers (the best of which would have been very high status objects), there are a number of extant trenchers with prints applied.

Once such is related to the uncut print above – as far as I can surmise, the trencher below has the original image by Crispijn de Passe, while the unused print above has been copied by transfer, and is thus reversed. Observation of the image below reveals a greater skill with both drawing and engraving, evident through the hand colouring. The print has been trimmed, and the verse desired has been applied by hand. The print is attached to the wooden trencher, coloured, and then sealed to protect it.

January, from a set of 12 wooden trenchers representing Labours of the Months

Print by Crispijn de Passe the Elder

Wooden trenchers decorated with engraving, pasted and hand-coloured, diameter 149 mm

Wooden case, diameter 186 mm

Flemish style, England c1620-30

The example below, from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, is a wonderful example of a print applied to wood, coloured (in a rather basic but effective way), and then sealed to protect the finished trencher. It has one circle of text kept as part of the print, and another added, presumably to further personalise the item:

Trencher with applied print of the Persian Sibyl

Wood, with print by Crispijn de Passe applied, hand-coloured, and inscribed in black ink, diameter 135 mm

English made object using Dutch print, c1601-25

In researching and searching for extant examples, there also seems to be a number of trenchers which I suspect to be made using prints, but which have not currently been identified as such in collections. This is no criticism of the museum/s in question, as many people conducting research in their particular field have come across the same issue. Often, items have been appraised once, usually when first brought into a collection, and not appraised again for a very long time – while research in the field continues to expand.

To that end, I very firmly suspect that this trencher in a Norfolk museum has a print applied to the surface:

Banqueting trencher

Wooden, painted, possibly with print applied, diameter 151 mm

England, late 16th century

If one looks carefully at the lower right edge, and around the perimeter, it is possible to see damage to the image which looks remarkably like a tear, or insect damage, with a section of the print missing and exposing the wood below.

Above: detail from the Norfolk museum trencher

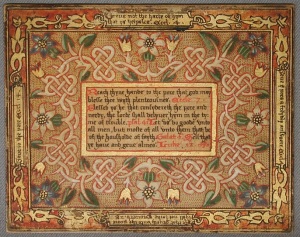

And so onto my own goal of recreating a set of Elizabethan trenchers… When approaching this project, my aim was not only to create objects which incorporate prints into a useful item, but to have created something I find aesthetically pleasing on a personal level. To that end, I decided to take the aesthetic of the painted trenchers, which are primarily executed with decorative floral and knotwork designs, and apply them to the printing process. The extant trenchers and prints referred to in this article all date from a time period in which mass-produced roundel prints were produced, so to me, as a printer, it is plausible that a set of floral trencher prints could have been produced. In looking at various examples, I decided on a lovely set of 12 which exist in the British Museum as my working design:

Set of 12 trenchers in box

Wooden, painted and gilded, trencher diameter 136 mm (varies slightly),

Wooden box, diameter 171 mm

England, c1600

The second article on this topic, Outlining the Process, can be found here.

I have seen pictures of the box set before. I even saved some for when I ever have enough time to make them for myself.

This is a very cool project.

Pingback: Recreating a set of Elizabethan Trencher – Outlining the Process | 21st Century Renaissance Printmaker

I would love to read this article, however the strongly textured background makes it very difficult to read the text, especially when the text is mid grey against a mottled grey background..

Hello Jane – thanks for your feedback. Is the plain background better? I would like to move back to a patterned background but will try to make it much paler, something I have to do with the original image, it doesn’t seem to be possible to edit within wordpress. Another reader has had the same issue as well.